What we manufacture?

Which brands we as distributor?

WHO ARE WE ?

-Leading Medium Voltage Electrical Devices And Switchgears Supplier.

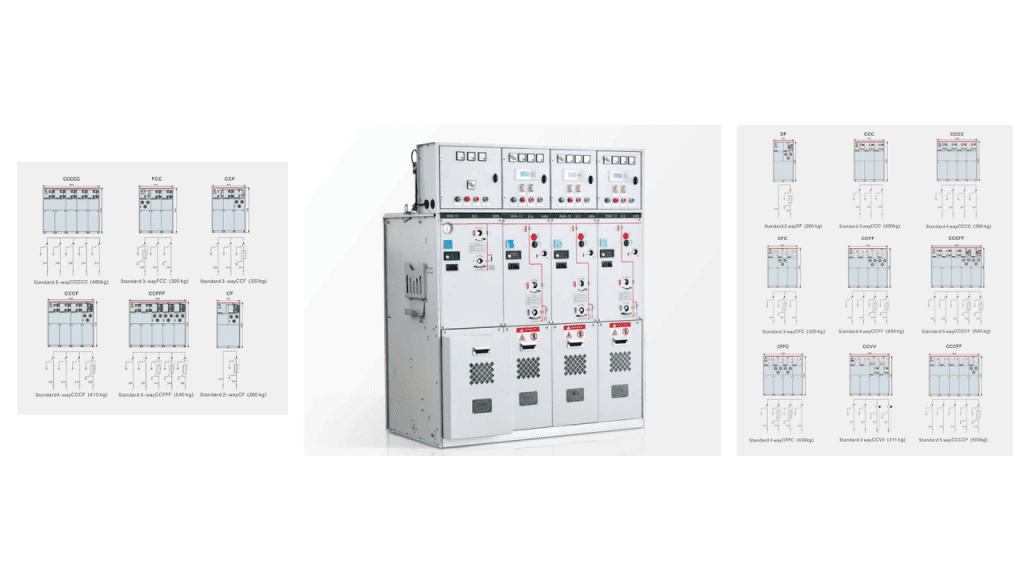

-Main product series are: Indoor & Outdoor Vacuum Circuit Breaker(VCB/CB),Load Break Switch(LBS);Outdoor Auto-recloser; SF6/SF6 free Ring Main Unit and Gas tank;Metal-clad Switchgear;

-Direct supply from the origin, Most competitive price, Efficient delivery.

-With rich industry resources and experience in the power and electrical industry.

-Official Authorized Distributor of world leading brand-EATON and Chinese leading transformer brand-QRE.

WHAT DO WE DO ?

-Our Mission

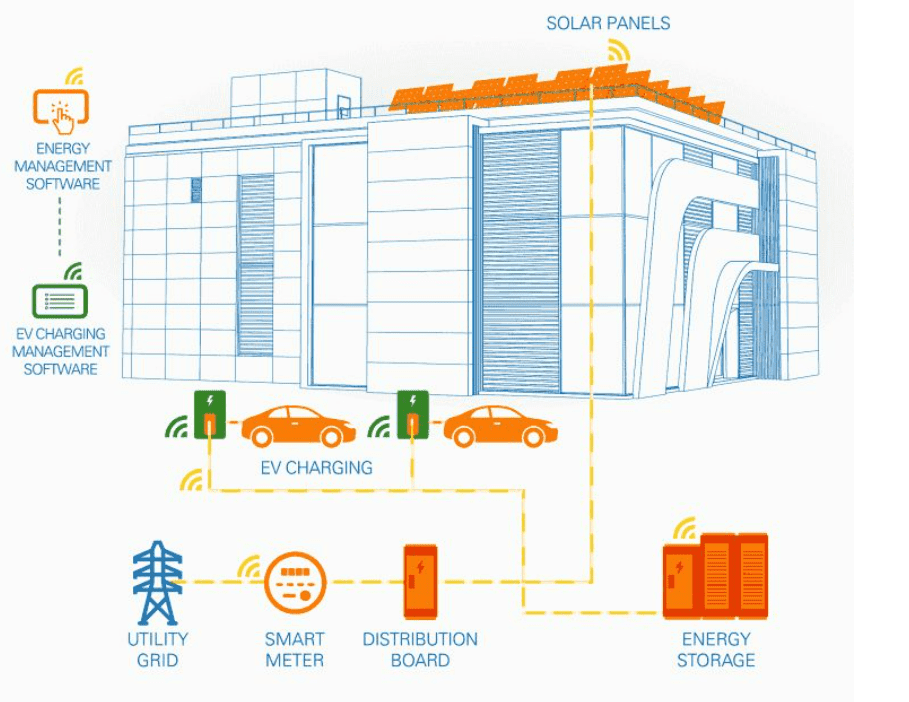

Make green power supply more safe and efficient

-Our Vision

Become a one-stop high-quality supply chain and professional service provider in the green power industry

Cooperative Partner

Manufacturing Factory

Environmentally Friendly Factory

R&D, manufacturing, and production of environmentally friendly series of switches and switchgear.

Vacuum Circuit Breaker Factory

R&D, manufacturing and production of vacuum circuit breakers, side-mounted circuit breakers, circuit breaker mechanisms, etc.

Outdoor Switch Factory

R&D, manufacturing and production of outdoor circuit breakers, reclosers, load switches, disconnectors, lightning arresters, etc.

Client Visits

Why Us

Quality Oriented

The company,quality oriented,has always selected well-known brands or high-quality product suppliers in the industry to ensure product quality; It saves you a lot of search and comparison.

Utmost Safety

All our products are manufactured in compliance with GB and IEC standards, with the reliable interlocking system for components, ensuring safe operation and personal safety.

Top support

Our team has several industrial experts and engineers, project manager with PPM certification. Most of teammember have worked in the low-voltage/medium voltage industry for many years. We have the ability to provide professional technical support.